June 2024

Threatened by geopolitical tensions and protectionist trade policies, globalization, the multi-decade megatrend that did so much to shape today’s economy, would appear to be, if not dying, then at least in retreat. For the global technology industry, one of the most potent symbols of our interconnected world, this shift has significant consequences.

If I was asked to name a poster child for globalization, I might opt for the semiconductor supply chain. Geographically diffuse yet deeply interconnected, this archipelago of hundreds of thousands of global suppliers and manufacturers is a hymn to the benefits of specialization and comparative advantage. Hyper efficient and cost effective, for decades it was a model that served the technology industry and wider economy well.

Less discussed were the fragilities inherent in such a dispersed and, at times, opaque structure. In an era when globalization was in the ascendancy, this was perhaps understandable – the risk of severe disruption to such a well-oiled machine seemed remote. In the present era of pandemics, protectionism and elevated geopolitical risks, this optimism can look a little like complacency.

As the merits of this hyper-globalized supply chain come under increasing scrutiny, any conversation about its future is more likely to involve talk of resilience and ‘de-risking’ than efficiency. It is a shift in emphasis that could have profound consequences. But how realistic is de-risking really and what might it cost, both financially and in terms of efficiency?

NVIDIA’S STUPOR MUNDI

The new Nvidia DGX B200 is a wonder of modern technology. A single, unified artificial intelligence (AI) platform that enables businesses to handle vast datasets at every stage of the AI pipeline, it is considered to be the most powerful system of its kind ever assembled, significantly more so than its predecessor the DGX H100.

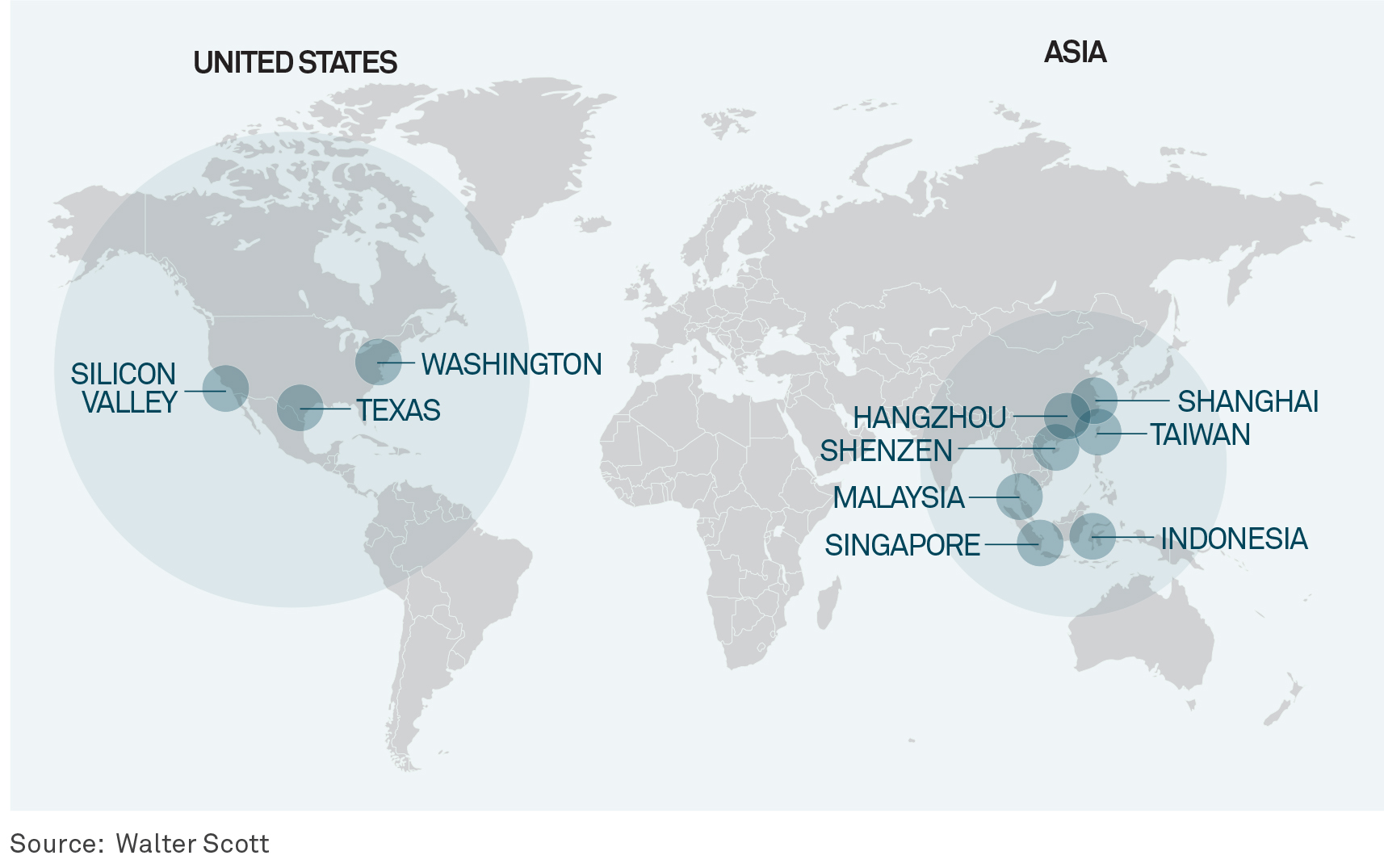

WALTER SCOTT SEMICONDUCTOR SUPPLY CHAIN RESEARCH

Underpinning the DGX B200 is the Nvidia-designed GB200 semiconductor, which while unquestionably a testament to the innovative genius of Silicon Valley, also happens to be manufactured by Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (TSMC) in Taiwan. So too the overwhelming majority of the tens of thousands of components that comprise the DGX B200 system.

In truth, the DGX B200 is only possible because of an elaborate global supply chain comprising myriad stages. So too any number of today’s technological products and systems, from data centers and commercial airliners to medical equipment and solar panels.

Take the humble smartphone. Its semiconductors are likely to have been designed in the West but manufactured, packaged and tested in Taiwan or China. Assembly of the finished product probably took place in a factory in China, India or Vietnam.

To state the obvious, this routing of many hundreds, or in the case of the DGX B200, many thousands of parts through a network of dispersed suppliers is hugely complicated. Even if just one component fails to turn up on time and in the correct location, disruption ensues. Yet the efficacy of today’s supply chains has served to conceal their complexity, leading some to underestimate the challenge of de-risking.

TIME AND MONEY

To reorient the existing technology supply chain to materially reduce reliance on specific geographical areas, most notably China and Taiwan (the so-called China Plus One1 strategy ), will take time and involve a huge amount of expense. What we have in situ today has evolved over many years, a hyper-efficient structure driven by the rigorous logic of market forces. Unpicking it is akin to swimming upstream.

TSMC’s founder and former chairman Morris Chang may have been exaggerating to prove a point when he stated that TSMC chips manufactured in the US would cost twice as much as those produced in Taiwan, but he was not wrong in implying that they will be considerably more expensive.

To some extent, this will be the result of extra upfront capital expenditure. When complete, TSMC’s fabrication plant (fab) in Arizona is expected to have cost as much as four-to-five times more to build than a fab in Taiwan. It is anticipated, however, that a good proportion of this will be offset by government subsidies and tax credits. This should also prove the case in Japan and Europe, where governments are similarly providing significant subsidies and tax breaks to encourage onshore manufacturing. More onerous are likely to be the higher operating costs incurred by manufacturing outside Taiwan. To understand why, a trip to Hsinchu, Taiwan’s Silicon Valley, is explanatory.

A short bullet train-ride from the capital Taipei, Hsinchu is home to thousands of companies involved at various stages of the technology supply chain, from suppliers of plastics, ceramics and specialty chemicals to passive components such as the resistors, capacitors, printed circuit boards, and advanced cooling systems used in Nvidia’s DGX B200. Hsinchu is also home to a highly specialized workforce that runs into the hundreds of thousands. This clustering of companies and people is incredibly efficient and cost effective. Replicating such an ecosystem elsewhere would take decades.

But there is another operational factor at play in Hsinchu that other countries may struggle to recreate. In Hsinchu, the fabs run all day and all night, manned by an army of people prepared to work long and antisocial hours. In short, the work-life balance of the average semiconductor engineer in Taiwan could best be described as sub-optimal. It is hard to imagine US and European workers embracing such a grueling work culture. So, on top of structurally higher wages in the US and Europe, TSMC will also likely be dealing with a structurally less productive workforce. This will likely lead to higher chip prices, at least in the near-to-medium term.

There are similar challenges at the ‘downstream’ stage of the process. Speaking with companies such as Foxconn and Pegatron, both heavily involved in the manufacture of products such as smartphones, consumer electronics and electric vehicles, it was clear that while there is real impetus behind the efforts of downstream players to diversify production, they are still heavily reliant on China. In time, the likes of India, Vietnam, Malaysia, Mexico and Indonesia should all prove alternative sources of low-cost manufacturing, but for now, none can match China for scale and productivity.

All of this should disabuse anyone still laboring under the assumption that de-risking is a quick fix. It is wholly unrealistic to think that production can simply be picked up and moved elsewhere easily, or alternative suppliers readily sourced in other locations. This is too specialized a supply chain, and capacity is not interchangeable. The entire process will create friction, generating cost inflation and inefficiencies as manufacturers push against natural market forces. Consumers do not want to pay more for their electronics and companies do not want to sacrifice margins. It is unlikely that both will get their way.

THE VENEER OF DE-RISKING

Nothing in my conversations with companies at all stages of the production process made me think the industry is anything less than fully committed to the process of de-risking. Management teams are acutely aware of the need to adapt to the demands of geopolitical reality and to do so quickly. They may not like it – after all, many are being asked to make their businesses less efficient – but they understand the rules of the game have changed and will not be changing back anytime soon.

On the current trajectory, some 34% of leading-edge fabrication is scheduled to happen outside Taiwan and China by 2027.2 This will enable Nvidia to say that some of its chips are made in the US. Apple will be able to tell its US customers that some of its phones are made in India rather than China. But in truth, this will be akin to a veneer of de-risking; Western companies will still be heavily dependent on Taiwan and China. Even on a ten-year horizon, while a more material degree of de-risking is possible with a lot of hard work and plentiful government subsidies, we believe both countries will continue to have a major presence across the supply chain.

1 China Plus One is the business strategy to avoid investing only in China and diversify business into other countries.

2 Visual Capitalist, Advanced Semiconductor Market Share by Country (2023-2027F)

All investments involve risk, including the possible loss of principal. Certain investments involve greater or unique risks that should be considered along with the objectives, fees, and expenses before investing. Company information is mentioned only for informational purposes and should not be construed as investment or any other advice. The holdings listed should not be considered recommendations to buy or sell a security.

BNY Mellon Investment Management is one of the world’s leading investment management organizations, encompassing BNY Mellon’s affiliated investment management firms and global distribution companies. BNY Mellon is the corporate brand of The Bank of New York Mellon Corporation and may also be used as a generic term to reference the corporation as a whole or its various subsidiaries generally.

This material has been provided for informational purposes only and should not be construed as investment advice or a recommendation of any particular investment product, strategy, investment manager or account arrangement, and should not serve as a primary basis for investment decisions.

Prospective investors should consult a legal, tax or financial professional in order to determine whether any investment product, strategy or service is appropriate for their particular circumstances. Views expressed are those of the author stated and do not reflect views of other managers or the firm overall. Views are current as of the date of this publication and subject to change.

The information is based on current market conditions, which will fluctuate and may be superseded by subsequent market events or for other reasons. References to specific securities, asset classes and financial markets are for illustrative purposes only and are not intended to be and should not be interpreted as recommendations. Information contained herein has been obtained from sources believed to be reliable, but not guaranteed. No part of this material may be reproduced in any form, or referred to in any other publication, without express written permission.

Walter Scott & Partners Limited (“Walter Scott”) is an investment management firm authorized and regulated in the United Kingdom by the Financial Conduct Authority in the conduct of investment business. Walter Scott is a subsidiary of The Bank of New York Mellon Corporation.

© 2024 BNY Mellon Securities Corporation, distributor, 240 Greenwich Street, 9th Floor, New York, NY 10286

MARK-546885-2024-05-15